Heartworm – Game Review

With chunky, pixelated graphics; tank controls; and stiff, awkward dialogue, Heartworm would have been right at home in the late 90s and early 2000s, when Resident Evil and Silent Hill were forging the survival horror genre. It’s a callback to those days—one of many indie games in recent years trying their hand at recapturing what made the genre so exciting early on—and if it came out back then it would have been a worthy entry to the genre.

We’ve come a long way though, and while it’s true that Heartworm might be a better game than Deep Fear, Fear Effect, and whatever else the rest of the genre had to offer back then, it’s also a far cry from the best of what’s come since.

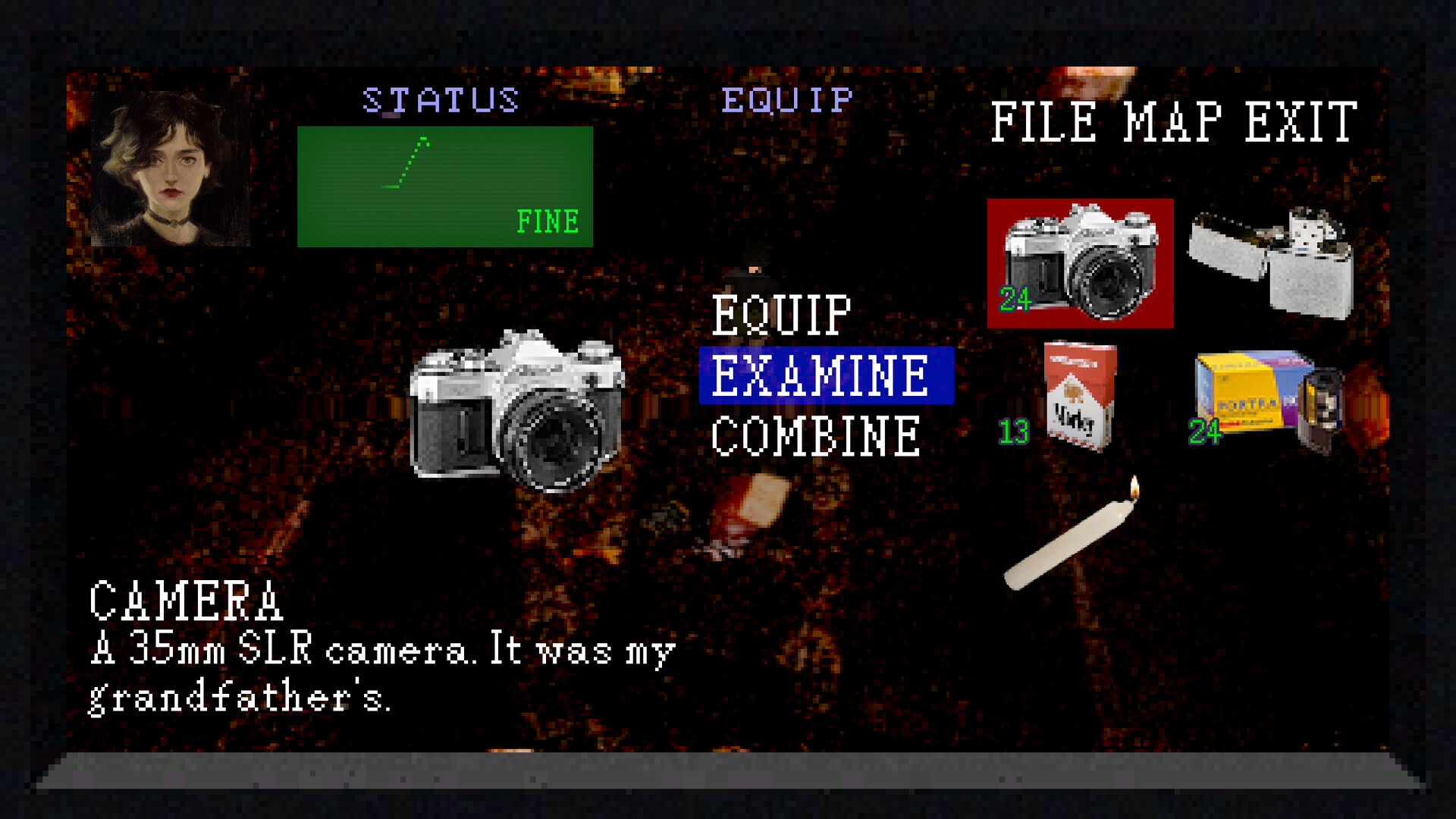

You play as Sam, a young girl traveling to an abandoned house in the woods. According to legends, this house is a portal to the afterlife. It’s both an opportunity to see the loved ones who have passed on, and, most likely, a one-way trip. Despite the risk, Sam drives out to this house with nothing more than a camera and a pack of cigarettes, ready for whatever might come, in hopes of finding someone who left her behind.

It’s an intriguing premise that feels underutilized. The world Sam falls into is a mish-mash of memories, a lifetime of moments and places duct-taped together in a dream-logic way. Sam will explain to us that a house is in the wrong spot or the woods look like a place her grandfather used to take her, but it took me most of the game to even figure out what her purpose was. Heartworm offers some light character and world-building, delivered through some awkward voice acting, but little else to chew on from a story perspective.

This genre is no stranger to minimal storytelling though, and that would be an easily forgiven issue if the rest of the offering was stronger. Unfortunately, the problems bleed into every element of the game.

Armed with a camera, Sam has film for ammo and fights off enemies by taking their photo. Whether they are a ghostly phantom made of static, a dog covered in weeds, or a drooling monster reminiscent of Resident Evil’s “Lickers”, every enemy in Heartworm is vulnerable to Sam’s camera. The result is that what should be a unique, non-violent twist on the genre, reminiscent of Fatal Frame, is mechanically identical to shooting enemies with a gun.

Even that could have been forgivable if the combat mechanics had more depth. However your toolkit never evolves much beyond what you have at the start of the game. It feels like going through the entirety of a Resident Evil game with nothing but the starting pistol. And even then, most Resident Evil games have enemies that react differently depending on where the pistol bullets hit them. Here, you line up the camera, the reticule turns red, and you shoot 4-5 times until the enemy goes down.

I wish I could tell you that Heartworm makes up for weak combat mechanics and storytelling by offering fascinating puzzles and exciting exploration, but it just wouldn’t be true. The world design of Heartworm is built on that aforementioned dream-logic. You’ll go through a door in a hallway and end up in a huge field in the woods, then open another door and end up in a hospital. This would be cool in a linear game, but Heartworm is a game about non-linear exploration with tank controls and fixed camera positions. The constantly shifting camera angles are combined with environments that have no logical flow. It feels like you’re playing one of those Zelda randomizer mods that load a random room every time you go through a new door.

The only way to keep the environment straight is to go into the map between every single room. Even then, the map itself can be confusing as it doesn’t show you which way Sam is facing or where she is in the room. Eventually you get used to navigating the environments, but by then it’s usually time to wrap things up and move onto the next confusing area.

The puzzles are largely inoffensive. Sometimes they require a pen and paper or a good memory, but they’re generally not a hard blocker and can even be satisfying to solve. But even here, in this one element that is mostly fine, Heartworm can’t seem to avoid a blunder. One late game puzzle combines some notetaking and exploration with a 12-panel sliding puzzle that must be solved to progress. There are certain puzzle types that you shouldn’t force on your audience, and mandatory sliding puzzles in a horror game should really be considered a game design taboo. I could imagine some players tapping out and never finishing the game because of a puzzle like this.

The downfall of Heartworm is that while it paints with Resident Evil’s toolbox, it doesn’t have the artistry or technique needed to achieve the same effect. There is a fundamental misunderstanding about why Resident Evil games combined their camera angles and combat with tight corridors and a logical layout. I haven’t played the original Resident Evil in at least 10 years but I could probably draw a map of most of the Spencer Mansion from the top of my head. In Heartworm I could barely remember where to go if I stepped away for a few minutes to use the bathroom.

Heartworm does not measure up to the games it takes inspiration from, nor does it measure up to contemporary indie survival horror games like Crow Country, Signalis, and Tormented Souls. It feels harsh to so heavily criticize a small indie effort in a genre I love, and I think some may be able to look past the flaws (and the advancements of better games in the genre) to find something to appreciate. Maybe they will connect with Sam or the story in a deeper way, or be wowed by the game’s grungy retro aesthetic. I don’t know. All I can say is that I can’t recommend playing it.