Slitterhead – Game Review

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had a great idea and watched it slip through my fingers as I put metaphorical pen to paper. It’s a story any creator is likely deeply familiar with. An amazing shower thought gets diluted by chores, phone notifications, work obligations—a myriad of distractions that, when you finally start to commit the idea to whatever format it’s meant for, the result isn’t nearly as cool as you imagined.

Now imagine that on the scale of a multi-million dollar video game project made over years, only possible through the collaboration of dozens of people, and it’s amazing any great idea ever makes it to launch day.

You can sense what the development team at Bokeh Game Studio had in their heads with Slitterhead, their new supernatural horror action game. Unfortunately, the game they put out, while fascinating at times, is brought low by how often its ambitions butt up against a limited scope.

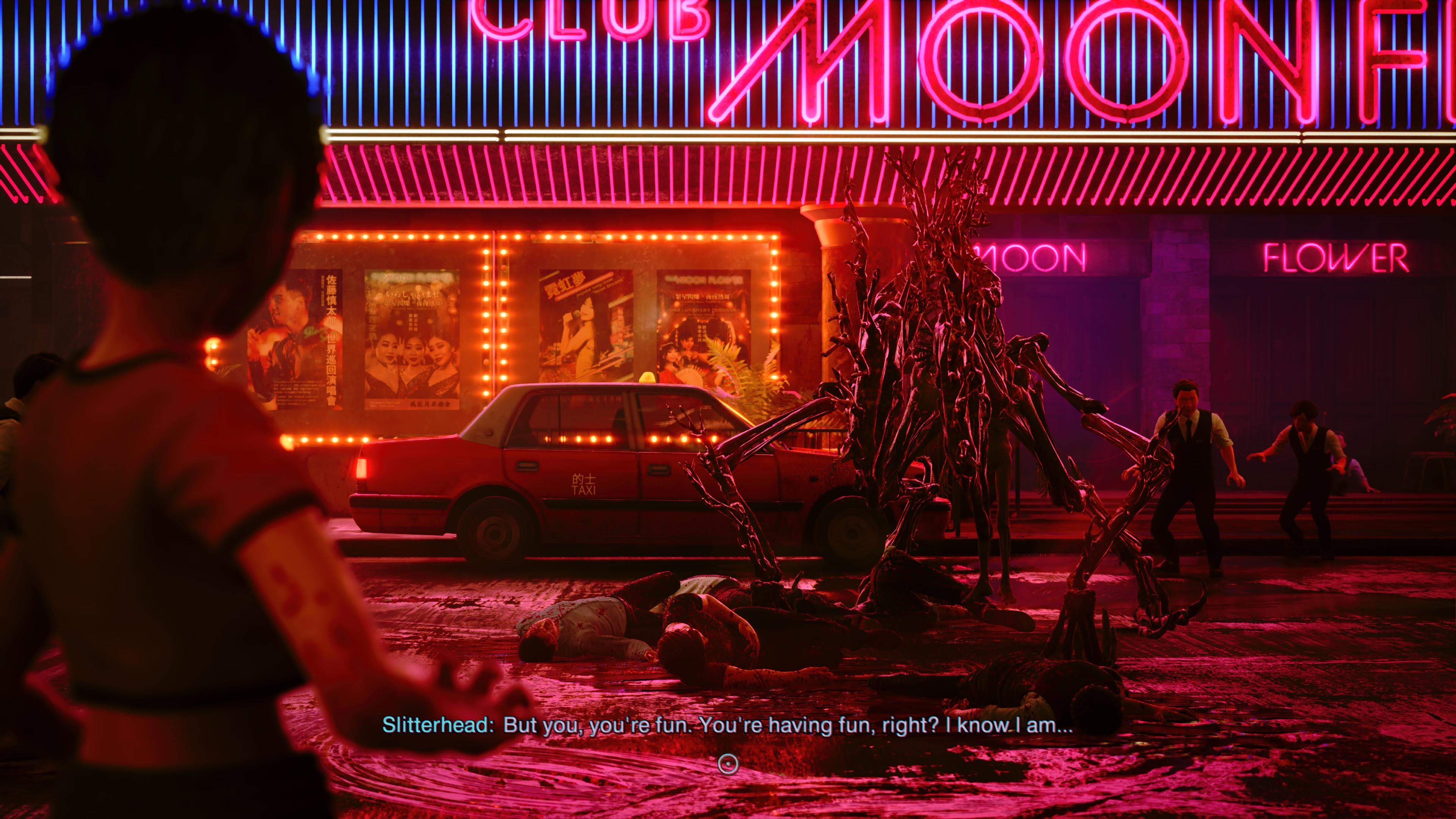

Slitterhead takes place in a fictionalized version of 1990s Hong Kong where strange creatures are killing people in the streets. Known as Slitterheads, they are reminiscent of the Las Plagas from Resident Evil 4. They burst from human heads, looking like bizarre tentacles that control the rest of the human body. When threatened, they transform further into huge insect-like monstrosities that wouldn’t look out of place in a John Carpenter film.

The vibe of this setting is key to what makes Slitterhead sticky despite the obvious issues I’ll get into later on. While Slitterhead lacks variety in its world design, the rain-slicked, nighttime cityscapes are so evocative that it’s hard to not get sucked in. Neon lights reflect in puddles, rickety shops fill the streets, and everything is packed in tight. People bustle through the main streets and side alleys, while the buildings feel like they’re right on top of each other.

You control what can best be described as a ghost or spirit. Nicknamed “Night Owl”, this entity can possess and take control of regular people. This allows you to jump from person to person as a mode of travel. In a bit of a sick twist, you can even possess a human on a rooftop, then jump off of the roof to possess someone else just before they hit the ground. Using the helpless, poor folks of this densely populated city to fight your war against the Slitterheads—who themselves use people and eat their brains—becomes a core thematic element of the story.

This ability to freely jump from body to body plays into the combat system. Slitterheads are far too strong for a regular person to fight. They can only take a couple of hits, and if you are still in a body when they die, you take damage as well. This makes it so the average pedestrian becomes cannon fodder as you try to overwhelm the Slitterheads from multiple angles.

When you possess someone you also extract some of their blood to form weapons. So from the very start you are already weakening these poor people before throwing them at the enemy. If a blood weapon breaks, you’ll have to extract blood again to remake it.

Some people are gifted with greater strength than the typical pedestrian. These “rarities” form the cast of characters Night Owl spends the majority of his time with. They also bring a suite of various powers to the combat system. Some are just more powerful attacks, but others play into the possession system, allowing you to call on crowds of humans to fight for you, or turn them into ticking time bombs.

While it takes far too long for the game to dole out all of these mechanics, the end result is actually pretty cool. There is a layer of strategy to the combat that makes it stand out from the crowd. Jump to a random mid-game fight in Slitterhead with a skilled player, and you’ll surely see something that looks unlike any other action game. It has the basics of a typical combat system like combos, dodge-rolls, and parrying, but it also adds in an almost real-time strategy layer over the top.

These fights are usually broken up with chase sequences. A Slitterhead will try to escape into the city, get some distance from you, and go back to human form so they can hide in the crowd. These chases can be pretty exhilarating at times, since the game allows you to catch up through possession, bouncing from body to body. On top of that, your possession allows humans to jump large distances, leaping along Hong Kong’s colorful signage to reach the rooftops above. There’s a momentum to these chases that feels like a stamp of director Keiichiro Toyama—whose prior games include the Gravity Rush series—even if they aren’t quite as impressive as his previous games’ traversal.

Between chases and fights, you’ll spend a surprising amount of time just talking to the cast of rarities. This happens mainly between missions in a simple map interface. When characters have new dialogue they’ll be marked on the map, and progressing these conversations is usually key to unlocking the next missions. You’ll see the characters going about some element of their daily lives—cooking dinner, studying for an exam, or working the register of a convenience store. At the same time, they’ll be having some philosophical argument with Night Owl about the violence they are participating in.

These sequences lack full voice acting. Instead, the characters will speak these weird whispering, mumbling sentence fragments as the actual dialogue appears on screen to be read. This gives you the gist of what these characters sound like, but it also gets pretty annoying and repetitive after a while. Especially since there is quite a lot of dialogue to read through. The game borders on feeling like a visual novel at times.

That repetition—a cost-saving measure in lieu of full voice-acting—is one example that infects almost every element of Slitterhead. I hope the game I’ve described so far sounds kind of awesome to you, because in many ways it is, but it isn’t the whole story.

Slitterhead simply doesn’t have enough unique content to support its systems, story ambitions, and 14-20 hour length. The entire game takes place within a handful of locations that are repeated over and over again. This is fine for a while, since the city design is so well-realized, but it starts to wear on you when you are hunting over the same handful of streets and going on the same exact chases dozens of times.

This would be forgivable if the variety was somewhere else, but it really isn’t. Even the core combat system gets tiresome because of a distinct lack of enemy variety. The game has three main enemy types: baby Slitterheads that act as fodder and essentially die in one hit, regular Slitterheads that all have a basic moveset, and the giant bug-like boss Slitterheads that all look the same but have some slight variety to their attack patterns. That means you essentially fight the same 3 enemies (plus the occasional human), for the entire length of the game.

Slitterhead also has a pretty slow start. I suspect many players may give up on it well before the combat gets interesting. It has that PS3-era quality where every time you walk a few feet forward, the game stops to tell you what to do next or introduce a tutorial. It felt like I played several hours before the full breadth of the gameplay was at my disposal.

The repetitive elements don’t stop with the level design or combat either. Even the storyline falls victim to this issue as it quickly introduces a time travel plot. It feels time travel was introduced as a direct result of budget constraints. Many missions are repeats of prior ones with changes to the story dialogue and branching moments as you try to travel back in time and fix things.

So you get a slow start as the game teaches you its mechanics followed by a pretty compelling middle chunk as you engage with all of these cool ideas for the first time. However, by the back half, I was really scratching my head as to why this game was still going. The final final chunk of the game requires you to replay several missions which are themselves just repeats of missions from the first chunk of the game. It is unforgivable padding to the extreme.

Despite all this, I had a good time with Slitterhead. I was baffled by the decisions to regurgitate the same content again and again rather than putting out a tighter 6-8 hour game, but I was also compelled by the interesting ideas that were there. This is a game that’s going for something fresh and unique, and while it doesn’t actually hit the mark, in 2024 taking a swing and failing can still be pretty damn interesting.

In another timeline, perhaps there is a Slitterhead that got the time and budget it needed to fully realize its ideas. That’s part of the weird charm of the game. It’s fun and entertaining enough that, rather than getting annoyed with it, it left me pondering what could have been. If only Bokeh Game Studio could go back and make some changes and additions, we could be talking about a new, innovative classic. Instead, Slitterhead is more of a weird curiosity, a collection of cool ideas that got lost in translation on the path from the developer’s brains to the final package.